What Do We Talk About When We Talk About Dreams?

Part one of a two-part exploration of the theme of dreams across the Honkaiverse

Before we begin, I would like to present a short riddle to you:

There are two types of dreams; the kind that you have when you are awake, and the kind that you have when you are asleep.

The first kind is indicative of aspirations we harbour during our waking hours, the kind that people mean when they ask you what your “dream job” is, or when they say that you are “living the dream”.

The second kind is perhaps a bit more… elusive and mysterious, the kind that people mean when they, still half-dazed from the fetters of their slumber, tell you: “I just had the strangest dream…”.

With that in mind, I would ask a question of you:

What do we talk about when we talk about dreams?

You don’t have to answer this right away, but do keep it in mind, as we will return to it later on.

With the loosely coinciding releases of Part 2 of Honkai Impact 3rd and the 2.0 update of Honkai Star Rail, the theme of dreams have been thrust to the forefront of the narrative of both games. By way of examples, the protagonist of Part 2 goes by the nickname of the “Dreamseeker”, while the Dreamscape of Penacony beckons at you as the “Dreamchaser”, and both Chapter 1 of Part 2 of HI3rd (Hundred Years of Solitary Shadow) as well as the new Trailblaze Mission in HSR (The Sound and the Fury) begin with dream sequences where the respective protagonists meet cryptic women who speak in riddles.12

I could be here all day long pointing out all the similarities between these two games in the context of their recent updates and this theme of dreams - and that is in fact part of the point of the second part of this article - so let me stop there for now.

Either way, this is far from the first time that dreams have appeared as a theme in the narratives of games that fall within the umbrella of the Honkaiverse, as dreams have always been a subtle, yet powerful part of HI3rd’s narrative throughout Part 1, for example. Therefore, I would like to explore what these stories have to say about dreams, what they mean, what they tell us about our deepest desires and our greatest fears, about the workings of our psyche in general, and perhaps even about life, death, and the universe itself.

This article will be split into two parts, starting (mostly) with Part 1 of HI3rd here in the first part, then moving on to the similarities - and differences - between Part 2 of HI3rd and HSR’s 2.0 storyline (so far) in the second part.

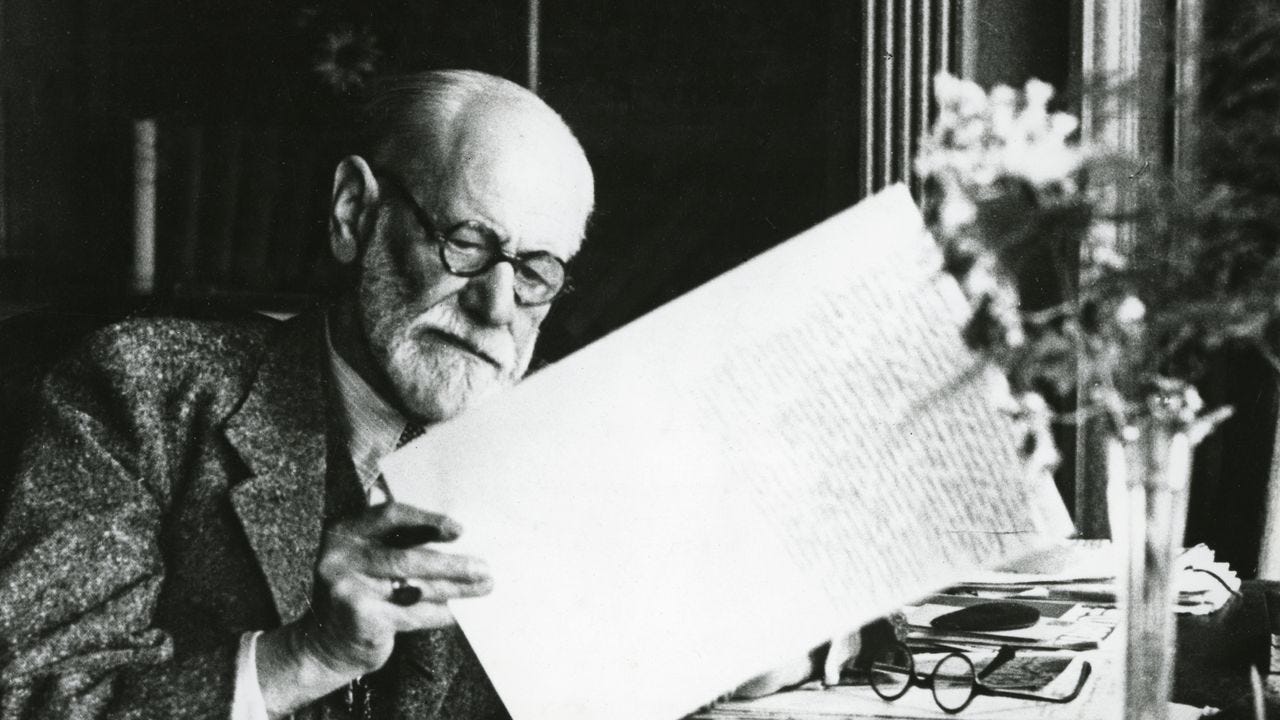

Freudian Psychoanalysis in Penacony

If you’ve been paying attention to HSR’s 2.0 update and storyline as well as the official content surrounding its release, you may have noticed a few references to Sigmund Freud and his infamous theory; psychoanalysis. For example, Dr Edward - the giant eyeball in Penacony’s Dreamscape Sales Store - is supposedly capable of knowing things about you through “the magic of psychoanalysis”, and there is also a hidden achievement in the game called ‘Introduction to Psychoanalysis’.34

Another example would be some of the soundtrack names throughout Penacony. The soundtrack that plays in the lobby of The Reverie is called ‘Realitätsprinzip’, which is German for ‘reality principle’, and the soundtrack that plays in the rooms of The Reverie is called ‘Lustprinzip’, which is German for ‘pleasure principle’.56 These are both important concepts in psychoanalysis, as we will see shortly.

Lastly, in the official HSR video ‘Knowing the Universe - “Approaching Dreams”’, Dr Edvard Moser - the Nobel Prize-winning Norwegian neuroscientist who was brought in as a guest - makes explicit reference to Freud’s use of hypnosis in his psychoanalytic method.7 I wouldn’t be surprised if there were more references to psychoanalysis in Penacony that I haven’t found yet, but you get the point.

Considering that miHoYo themselves seem quite familiar with psychoanalysis and are even explicitly using it to construct their narratives - or for one of them, at least - it seems fair for us to use it as our primary framework of analysis with which to explore the theme of dreams within the narrative of these two games. For those of you who are sceptical of psychoanalysis however, rest assured that we won’t be using it uncritically; and in fact, part of the aim of this article is to explore the notion of dreams beyond psychoanalysis. In other words, it is merely our starting point. As my psychoanalysis professor was fond of emphasising: Freud is often wrong, but he is almost always wrong in an interesting way.

As I’ve said earlier, although I have, and will be referencing HSR here and there, this article, which is the first part of this two-part article, will focus mostly on Part 1 of HI3rd.

Dream Interpretation and the Two Principles

With that in mind, let’s start with what I mentioned earlier as one of the most important concepts in Freud’s theory of psychoanalysis: the pleasure principle. Otherwise known as the unpleasure principle or the pleasure-unpleasure principle, it is the simple psychological tendency to gain pleasure and avoid displeasure. Freud considered this to be the most dominant tendency in the processes of the unconscious mind, which he in turn considered to be the primary processes of the human psyche.

“We psychologists grounded in psychoanalysis have become accustomed to taking as our starting point unconscious psychic processes. […] We consider these to be the older, primary psychic processes, remnants of a phase of development in which they were the only kind. The highest tendency obeyed by these primary processes is easy to identify; we call it the pleasure-unpleasure principle (or the pleasure principle for short). These processes strive to gain pleasure; our psychic activity draws back from any action that might arouse unpleasure.” - Freud, ‘Formulations on the Two Principles of Psychic Functioning’ (1911), in The Penguin Freud Reader, pp. 414 - 415.8

For Freud, the pleasure principle is in fact an essential driving force of life, for ‘pleasure’ and ‘unpleasure’ in this context is meant in its broadest and most general meaning. For example, we feel hungry when we need food, which Freud takes to be a form of displeasure, and as a result, we seek out food; when we eat, we then feel our hunger satiated, which is a form of pleasure. In this sense, the pleasure principle is quite akin to an instinct for survival and self-preservation. Of course, although this is the most dominant tendency within the unconscious, it isn’t the only one.

As you may have already guessed, there is a second principle, which is called the reality principle. According to Freud, the nature of reality is such that it hampers the fulfilment of our desires to a certain extent. For example, when we are hungry, we can’t satiate that hunger as soon as we feel it; we first have to procure, process, and eat some food. Therefore, the psyche must at once learn to reckon with the delayed gratification of pleasure that is caused by reality, and to also find a way to actualize its wishes into reality and thereby gain the pleasure that it seeks.

“[...] Whatever was thought of (wished for) was simply hallucinated [...] it was due only to the failure of the anticipated satisfaction, the disillusionment as it were, that this attempt at satisfaction by means of hallucination was abandoned. Instead, the psychic apparatus had to resolve to form an idea of the real circumstances in the outside world and to endeavour actually to change them. With this, a new principle of psychic activity was initiated; now ideas were formed no longer of what was pleasant, but of what was real, even if this happened to be unpleasant.” - Freud, ‘Formulations on the Two Principles of Psychic Functioning’ (1911), in The Penguin Freud Reader, p. 415.9

And now, we arrive at the notion of dreams: for Freud, “a dream is the fulfilment of a wish”, which we failed to fulfil in reality, during our waking hours.10 Even in the case of nightmares, which present to us dreams that clearly seem to be the frustration of a wish or even something that we straightforwardly do not wish for - what Freud called ‘counter-wish dreams’ - they still belie a wish of ours that has been subject to distortion in the unconscious processes of our psyche.

As foreshadowing for the second part of this article, we may perhaps also think of this as an answer to the question: “Why does life slumber?”, which, if you recall, came along with the invitation to Penacony in HSR’s 2.0 story. To put it simply, life slumbers because life is such that it is fundamentally driven by the psychic functioning of our desires, whereas reality is such that it fundamentally limits the fulfilment of those desires; hence, dreams take over where reality has failed in that regard.

In any case, with all this in mind - at the risk of reproducing Freud’s mistakes, perhaps somewhat intentionally - let’s do a bit of dream interpretation of our own, shall we?

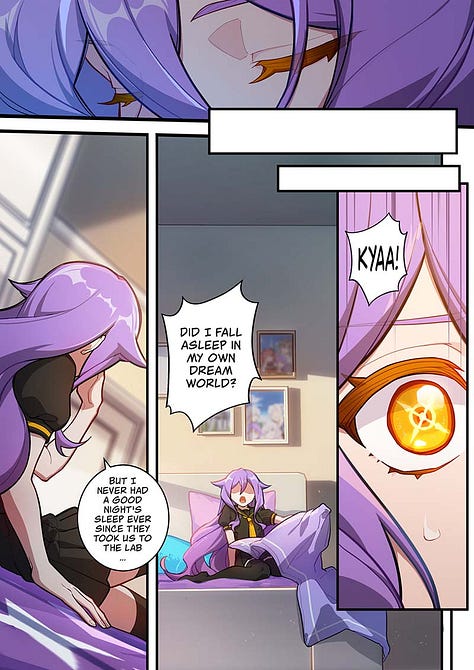

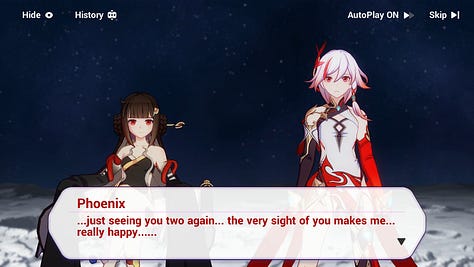

There are plenty of examples that we can draw from throughout Part 1 of HI3rd. For our first example, let us turn to the Second Eruption manga; specifically, the part where Sirin took over Fenghuang Down’s powers after narrowly surviving the ‘battle’ against Fu Hua, and attempted to use it to create a nightmare with which to torment Siegfried and Cecilia. Of course, she instead created an ideal dream world where the Honkai is gone and everyone lives happily ever after, much to her own chagrin. In this case, it is very obvious that this dream world betrayed Sirin’s deep-seated unconscious desires for a happy life with a family due to the fact that she has been deprived of that very thing.11

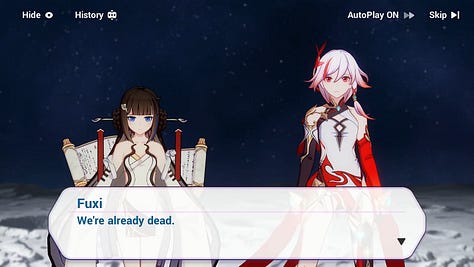

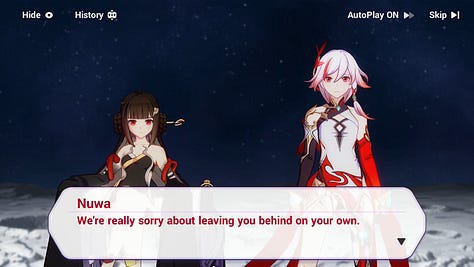

Likewise, we can see this same logic of dreams as wish-fulfilment play out in the memory of Fu Hua’s dream within a feather of Fenghuang Down in Chapter 20, whereby she reunited with Fuxi and Nuwa long after the two of them have sacrificed their lives to stop Chiyou, indicating her desire to reunite with those long lost companions of hers. In fact, since that whole entire story arc is titled ‘Taixuan Dreams’, we may even think of all the memories that Kiana and Bronya sifted through in Mount Taixuan in Chapter 20 as dreams, which often do simply reproduce our memories wholesale, since memories are the material from which dreams were formed in the first place. Therefore, these dreams revealed Fu Hua’s yearning for the people that she had lost throughout her unimaginably long life.12

Although it’s more indirect, there are also examples of the reality principle at play within HI3rd’s narrative. It is implicitly contained within the previous example, but there is also the lyrics of the chorus for ‘Regression’, the theme song for the ‘Thus Spoke Apocalypse’ animated short:13

This is an indication of what Otto and Fu Hua experience as fellow immortals, though this also applies to us mortals: a reminder that however sweet the dream and however much we wish for it to be real, or to remain in the world constructed by our own minds where our deepest desires can be fulfilled, the dream must end, and the dreamer must awaken; the suffering reality inflicts upon us must return. After five centuries, Otto’s wish to reunite with Kallen eventually turned into a single-minded, destructive obsession, and Fu Hua had to wait for thousands more years not to reunite with her old companions, but to forge bonds with new ones. It is thus that desire takes its circuitous route through reality in order to attempt to reach its destination.

We can also see the distortion of desires manifesting through dreams at play with Kiana’s nightmares. One of the forms of distortion which can take place in our unconscious, according to Freud, is the playing out of the very thing which we do not wish for; and in this case, the wish that is hidden by our nightmares would be “the wish that [we] may be wrong”.14 The nightmares that plagued Kiana after the Herrscher of the Void’s awakening - of her companions dying by her own hands, and of the world lying in pieces at her feet - could certainly be construed as such, for it is the one thing that she wished not to come to pass.15

These nightmares continued to plague Kiana up to the Herrscher of Domination Arc, but if we look towards the very end of that story arc - in Chapter 25 - we can see one particular line that is notable in this regard:16

Of course, earlier in Chapter 25, we witnessed how Kiana struggled through and eventually managed to overcome the psychic trauma that she has been suffering from over the past half-year or so by then. The absence of dreams during her sleep at the end of this chapter thus seems to be a mark of the fact that she has surmounted her inner conflict with HoV.

And yet… are things really that simple?

Was it simply that Kiana successfully repressed the presence of HoV deeper into her unconscious mind, where she will no longer plague her with night terrors? Was it simply that the absence of dreams in her sleep was a psychic sigh of relief, a sense of security at the fact that her worst nightmares will not come to pass? Was it simply that she no longer yearned for Himeko’s presence and grieved the loss of her life?

Not even Freud thought that things were so simple.

So let us return to Freudian psychoanalysis; and this time, we’re diving deeper.

Beyond the Pleasure Principle - the Death Drive

Behind the two principles of psychic functioning that we discussed earlier lies a third psychic principle that Freud took for granted, as he himself had admitted: the principle of constancy, which in a sense is both the foundation and extension of the pleasure principle. We seek out pleasure and we avoid displeasure, and this impulse at once is triggered by and creates an unpleasurable tension described by the reality principle: we want something that we do not have, precisely because we do not have it; there is a tension between our desires and reality. The principle of constancy seeks to minimise this unpleasurable tension, or to at least keep it at a constant level, thus maintaining a state of equilibrium or stability in the psyche. Freud likened it to an economic logic of the psyche:

“In psychoanalytic theory we assume without further ado that the evolution of psychic processes is automatically regulated by the pleasure principle; that is to say, we believe that these processes are invariably triggered by an unpleasurable tension, and then follow a path such that their ultimate outcome represents a diminution of this tension, and hence a propensity to avoid unpleasure or to generate pleasure. When, in our study of psychic processes, we look at them with specific reference to this manner in which they evolve, we introduce the ‘economic’ perspective into our work.” - Freud, ‘Beyond the Pleasure Principle’ (1920), in The Penguin Freud Reader, p. 132.17

That being said, Freud later expressed doubt in this entire framework, stating that “the true situation [...] can only be that the pleasure principle exists as a strong tendency within the psyche, but is opposed by certain other forces or circumstances, so that the final outcome cannot possibly always accord with the said tendency in favour of pleasure.”18 As to what brought on this doubt, we need to look no further than the historical circumstances in which he wrote his seminal essay ‘Beyond the Pleasure Principle’ in 1920, which is precisely where he expressed these doubts and further developed his theory of psychoanalysis.

During the events of World War I and in its aftermath, quite understandably, Freud gained an influx of patients that were former soldiers suffering from Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD), which was then known as ‘traumatic neurosis’, or more informally as ‘shellshock’. One of the most distinct and well-known symptoms of PTSD is the involuntary recollection of the traumatic event(s) that caused it to begin with, often manifesting in recurring nightmares. Although Freud has extensively covered the topic of nightmares before - as we briefly touched on earlier - these symptoms of PTSD caused him to even go as far as to “start doubting the wish-fulfilling tendency of dreams in general.”19

You see, according to both the pleasure principle and the principle of constancy, the psyche should be repressing these traumatic memories into the depths of the unconscious instead of bringing them to the forefront seemingly with the same intensity as when the event first occurred; and yet, here we are. It seems that the assumptions Freud made about the human psyche - of the psychic domination of the pleasure principle, which seemed to be all too rational, like a psychological corollary of biological theories about the functioning of life through survival instincts, despite the irrationality of dreams and the unconscious whence it came - was still incomplete, and needed something else, something entirely different; what Freud proposed as “tendencies [...] that are arguably more primal than the pleasure principle, and quite independent from it”.20

Enter the death drive; it is quite simply life’s innate tendency towards its own death and self-destruction, the exact opposite of the instincts of self-preservation that we know as the pleasure principle, which Freud had recontextualized as the ‘life drives’ (Eros) in relation to this death drive (Thanatos). The latter might seem counterintuitive in comparison to the former, but once Freud delved into it, the logic seems to almost be bleakly self-evident. He darted through several different metaphors, analogies, and contexts to describe and explain this, but the most intuitive one is perhaps his conjectures on the notion of abiogenesis; the idea that the organic matter we know as life necessarily originated from inorganic matter - that is, ‘dead’ matter - and so must also eventually return to it, which is precisely what death is.

“If we may reasonably suppose, on the basis of all our experience without exception, that every living thing dies - reverts to the inorganic - for intrinsic reasons, then we can only say that the goal of all life is death, or to express it retrospectively: the inanimate existed before the animate.” Freud, ‘Beyond the Pleasure Principle’ (1920), in The Penguin Freud Reader, p. 166.21

To return to HI3rd, the nightmares that Kiana suffered from seem to me to be the symptoms of PTSD par excellence, irrespective of the influence of HoV. After all, I don’t think anyone would argue that she was profoundly traumatised after what she went through, helplessly watching her mentor die before her eyes, seemingly by her own hands. In the context of the death drive then, Kiana’s nightmares are driven by that innate tendency for self-destruction that we all carry deep within our unconscious mind, which dominate our psyche in the case of severe trauma. In fact, we may perhaps even go as far as to say that HoV, in all her vengeful glory, is the personification of this drive in Kiana’s psyche; especially after Chapter 25, where Kiana acknowledged that HoV is part of her, just as she is a part of Sirin.22

In fact, we could go even further yet: from Arc City to Nagazora, we came to learn that Kiana’s heroism was no longer a case of selfless martyrdom; she had become self-sacrificial to a fault, at times even actively suicidal, having already accepted her own death. She was willing to jump headfirst into danger and risk her own life for the sake of others; and if she died in the process, it’s all the better to her, for she considered herself to be the greatest threat to humanity. This wasn’t just a rational calculation, but a deep wound etched in her heart and psyche, and it was what would’ve allowed HoV to encroach into her mind, slowly break her spirit, and take control of her body, if it weren’t for her companions.23

And yet… once again, I must question whether things really are that simple.

Was it simply that ‘Kiana’ represented the Eros within her own unconscious, while HoV represented Thanatos? Was it simply that, when Kiana managed to resolve her inner turmoil with HoV, she successfully healed from her trauma and repressed the death drive back into the depths of her unconscious, and thereby reinstated the dominance of the pleasure principle in her psyche? Was it simply that Kiana gained a notion of heroism that no longer involved self-sacrifice?

It seems that we have reproduced the circumstances of our previous assumptions, merely swapping out ‘displeasure’ with ‘death’. As Freud himself had implied however, the death drive is a matter of an entirely different economy of the psyche than the one that he has worked towards. ‘Beyond the Pleasure Principle’ is perhaps Freud’s most interesting text because of this; it is where he is at his most uncertain, not only regarding his own psychoanalytic framework, but also the fundamental philosophical assumptions underpinning that entire framework. In the many examples he used to describe and explain a model of the psyche that includes the death drive, he went on to question the interiority and exteriority of the psyche, the structure of its organisation, the distinction - or lack thereof - between life and death, and even the very notion of a beginning and an endings, or any unity of the psyche at all.

Indeed, what is truly at stake here is, in fact, an assumption that is perhaps even more foundational to Freud’s entire enterprise of psychoanalysis: which is to say, the conception of the unity of the psyche as an organism, which has as its most essential tendency the drive towards self-preservation, equilibrium, and stability. This assumption is what begins to fall apart upon contact with the death drive, precisely because the death drive contradicts that tendency, and it wasn’t something Freud could empirically ignore. Of course, the death drive on its own is not enough for a critique of psychoanalysis; for that, we’ll have to go further, and this is where we really get to the crux of what HI3rd has to say about the nature of dreams and desire.

Critique of Freud - Beyond the Death Drive?

Psychoanalysis has been criticised for as long as it has existed - a cursory glance at most of Freud’s work will reveal his spirited engagement with his sceptical contemporaries - and it has not stopped since then. At this point, there is around a century’s worth of criticism within and surrounding the field of psychoanalysis, and here, I would like to draw attention to what I consider to be one of the most effective critiques of it yet, for it cuts right into those fundamental philosophical assumptions that I just mentioned earlier. I’m referring about the joint work of the philosopher Gilles Deleuze and the psychoanalyst Felix Guattari; specifically, their two-volume magnum opus, titled: Capitalism and Schizophrenia (Anti-Oedipus and A Thousand Plateaus).

Capitalism and Schizophrenia is widely considered to be the most impenetrable and esoteric texts that French philosophy has to offer - despite the stiff competition - but for our purposes, we’ll be focusing on the broader strokes of their critique on those philosophical assumptions underpinning psychoanalysis.

First and foremost, Deleuze and Guattari deny any notion of unity in the psyche in the form of the ego, the self, identity, consciousness, individuals, and so on and so forth. In fact, they consider these things as phantasms or mere elements of the unconscious, whereas the real primary processes of the unconscious function in terms of multiplicities, which is to say the multiple as a substantive that do not presuppose a whole and are irreducible to its constituent elements; it is not a matter of individuals, nor even of collectives (as in a Jungian notion of a ‘collective unconscious’), for that could also presume a unity of the psyche.

As a consequence, where there is no self, there is no such thing as self-preservation or self-destruction; instead, in the place of these tendencies that drive particular organisms, Deleuze and Guattari introduce a psychic ontology of partial objects and flows of desire, where desire flows not as a function of an ego or a self, nor even towards any given goal or destination - such as pleasure or death - but for the sake of the process itself:

“Desire constantly couples continuous flows and partial objects that are by nature fragmentary and fragmented. Desire causes the current to flow, itself flows in turn, and breaks the flows […] produced by partial objects and constantly cut off by other partial objects, which in turn produce other flows, interrupted by other partial objects. Every “object” presupposes the continuity of a flow; every flow, the fragmentation of the object.” - Deleuze and Guattari, Anti-Oedipus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia (1972) pp. 5-6.24

This is what Deleuze and Guattari mean whenever they mention ‘schizophrenia’: the schizophrenic as a clinical entity is a manifestation of this process of flow and fragmentation; after all, the term ‘schizophrenia’ originated from the Greek words ‘skhizein’ - meaning ‘to split’, as in ‘schism’ - and ‘phrēn’, meaning ‘mind’, though this process is not exclusive to people with schizophrenia, but instead underlies every conceivable process of the unconscious. This is also why they called this framework of theirs ‘schizoanalysis’ as opposed to Freud’s psychoanalysis, and they then go on to link all of this to the psychic economy of capitalism - hence, Capitalism and Schizophrenia - but that’s neither here nor there.

There is one last element of Deleuze and Guattari’s critique/framework that I also want to bring in here: the notion of becoming, which is precisely the process described above, but with additional connotations. ‘Becoming’ stands in direct contrast against ‘being’, which is the notion of a static state of existence proper to the stable identity of an ego and the self-preserving equilibrium of the organism. In other words, it’s a process of change, differentiation, and continuous variation, inseparable from the passage of time itself, that irrevocably alters the elements involved in it, opening them up to each other. Deleuze and Guattari gave the example of pollination, whereby the wasp that is carrying the pollen of an orchid is involved in a becoming-orchid, and the orchid whose pollen is carried by the wasp is in turn involved in a becoming-wasp. In relation to all these processes, “the self is only a threshold, a door, a becoming between two multiplicities”.25

At this point, it might be a bit difficult to see what all this has to do with dreams, but do keep in mind that dreams - as part of the processes of the psyche and the unconscious - are indeed very much involved in these multiplicities, becomings, flows of desire, and fragmentations of partial objects. I posit that we can already see these processes at work throughout HI3rd’s narrative, such as in the examples that I’ve given above.

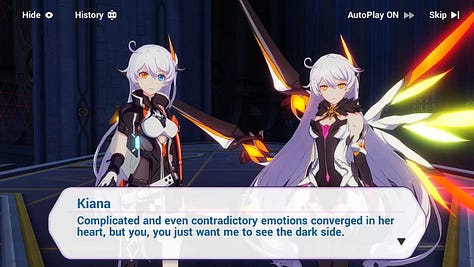

Throughout Kiana’s confrontation with HoV in Chapter 25, what was repeatedly emphasised and laid bare within the theatre of their shared unconscious is not the unity of their psyche, nor the existence of one true identity for either of them, but rather the multiplicity of the psychic processes at work underneath it all - memories, dreams, and desires alike - in which their egos are but mere elements. As Kiana herself said, Sirin’s wishes gave birth to two egos (her and HoV); and so in other words, it is desire that gives birth to the ego - a multiplicity of egos, even - and not the other way around.26

Since one is already several, two is a crowd. They are both Sirin, they are both Kiana Kaslana, they are both test subject K-423, they are both the Herrscher of the Void, and so on. All these identities make up who they both are, but they are not reducible to any single one of these identities, and nor do the sum total of all of these identities limit who they are; or perhaps more importantly, who they can become. Indeed, Kiana is even more than all of that: among other things, she is also a student of Murata Himeko, who went on to embody her dreams of changing this world, not as a fleeting fantasy of wish-fulfilment, nor as a nightmarish phantom of guilt and self-loathing, but as that very process of growth and becoming, which is the only way that life itself can proceed, utterly inseparable from reality and the passage of time. Of course, the same also applies in relation to the rest of her St Freya companions.27

This is how she came to a better understanding of the nature of her own sacrifice and heroism. We can no longer psychologically map it onto the notion of a death drive, for it is not simply a matter of dying for the sake of others, but also a matter of living for the sake of others - that is, for the sake of that which is not oneself - which we may indeed call a becoming; there is a becoming-Sirin of Kiana and a becoming-Kiana of Sirin, just as there is a becoming-Himeko of Kiana and a becoming-Kiana of Himeko. It is a desire that desires that which is not itself; a process of differentiation. As Dr Mei said to Prometheus in Act 3 of Chapter 32: “the nature of humanity is to sacrifice oneself for something else”; in other words, to enact its own growth through a gradual embrace with the Other and the abolition of the self, like a moth chasing a flame.28

Either way, the realisation of dreams in this manner does not necessarily entail the satisfaction of desires through its fulfilment, nor its final end through death, but rather of its breaks and its continuations alike. As Sirin’s purple feathers scattered across the skies of Nagazora, the dream that Kiana awakened from during her Graduation Trip marked not a wish fulfilled, but rather a wish continued out into the future. Sirin’s wish for love was the origin of Kiana’s life, and is itself the very life that she leads to this day - after all, she has experienced the most profound love that life has to offer alongside all the pain and suffering - but it’s hardly the end of her story, for she is still awaiting her return to the Earth where her loved ones are upon her moonlight throne.29

In fact, this is exactly the kind of ‘sacrifice’ that HI3rd’s narrative extols generally. Besides Kiana and Himeko, there is also Fu Hua, who lived and died (twice, even) for the sake of humanity and the people she loves. Likewise for her, the notion of multiplicities is strongly emphasised through the myriad identities that she has come to assume over the many millennia of her lifespan: the shy schoolgirl of the Previous Era, the MANTIS soldier of MOTH, the Celestial Phoenix, the guardian of humanity and the executor of Project Ember, the Shadow Knight of Schicksal, and last but not least, the student of St Freya.

One may even conjecture that Fu Hua’s relationship with Senti is similar to that between Sirin and Kiana in this regard, in that Senti is an entity that is quite distinct from Fu Hua, but is nevertheless a testament to the multiplicity of their unconscious; she was born from her desires, not necessarily for any particular thing, but precisely as a process of differentiation and becoming that naturally occurs with the passage of time. This is exactly what those Taixuan Dreams revealed to us: a yearning not for the past, nor even for any specific destination, but as a road stretching out towards the future, as the creation of that future that is still uncertain, yet to be, and filled with possibilities, where she would go on to meet her new companions.3031

Mei is another excellent example of this. The way she sacrificed her own joy and happiness and lived for the sake of another - that is, for Kiana - is quite plain to see; and just like Kiana, it wasn’t until later on that she came to a much better understanding of the nature of sacrifice, both her own as well as others’. Mei’s experiences with Elysia and the thirteen Flame Chasers in the Elysian Realm showed her that for them, death was not the end of the story, for the multiplicity of their desires contained the nascent seedlings of the future, which could only extend into said future with their passing, through the destruction of the Realm.32

Even those who seemed like ghosts of a bygone past had lived and died for the sake of future generations that hadn’t even been born yet; so as part of that future generation, Mei would become their successor who inherited their longing to embrace the future. Thus, it was those old dreams of the past that allowed her to meet Kiana halfway by respecting her agency, which includes her decision to sacrifice a decade of her life on the moon for humanity’s sake, and this, in turn, would carry her yearning into the future yet again; having transcended Finality, she still eagerly awaits Kiana’s return, beyond the open ‘ending’ of their story.33

We could even count Otto in on this too. Initially - as I briefly touched on earlier - his single-minded obsession of reuniting with Kallen seemed a perfect example of Freud’s psychoanalytic framework at work, where his dreams, to sweet to be true, represented the dominance of the pleasure principle within the unconscious, whereas his waking hours that took those dreams away represented the cruel pain of the reality principle. However, his desires seemed to have changed at some point in the story, as he ultimately decided to give up that nostalgic wish along with his own life in order to open up the possibilities of Kallen’s future once again.

On top of that, it’s no mere coincidence either that in doing so, Otto would also open up these possibilities to the many others whose futures he had foreclosed in the past, in his own branch of the world. In this regard, it would seem that his final words - “the other future will belong to her” - could very well apply not only to Kallen, for his regression to the past would signal the world moving forward, beckoning those who would inherit it. He no longer dreamed of the past and sought to shape his present reality according to those wishes; rather, much like everyone else, he began to yearn for what is to come, though he knew he had no place there. This sacrifice that precipitated the flourishing and reinvigoration of these future possibilities could not possibly be understood in terms of death; rather, it is precisely the processes that constitute life itself.3435

Last but not least, when it comes to the theme of dreams in HI3rd, there is an elephant in the room that we have yet to address throughout this article; and thus, we return here to Project Stigma and its Dreamland. In this context, the notion of dreams as a form of wish-fulfilment isn’t simply a case of a mistaken framework; rather, it is a false eternity that is akin to life imprisonment for all of humanity, the staunching of the flow of time through the staunching of the flows of desire via its perpetual and immediate fulfilment. This dream is something that the humanity of the Current Era must resist if they are to overcome Project Stigma; and there is a conflicting dynamic here that, once again, may well map onto Tagore’s two philosophies, which I explored in my previous article.

Indeed, we can clearly see that humanity quite simply and wholeheartedly rejected this idealised fantasy with barely any guidance or external intervention, even for those who seemed to desperately need it to escape the suffering that reality inflicted upon them in their waking hours. As the Dreamland inevitably shatters with time, all of humanity would be involved in this process of becoming; and since, as Dr Mei said, the nature of humanity is to sacrifice oneself for something else, it is through this process of becoming that this new humanity would seek out that which is not itself, that which is non-human. In overcoming Project Stigma and transcending Finality, there is also a becoming-Honkai of humanity, and a becoming-humanity of the Honkai; and once again, this process is exemplified in the Herrschers of Humanity.36

Speaking of Project Stigma; Kevin, its executor, has had the ability to dream taken away from him all the way back in the Previous Era, and he thus hasn’t had one in fifty thousand years. It is a mark of the hold that his past had on him, and how it haunted him with every step he took. And yet, as the new generation of humanity awakened from their collective fantasy to embrace the future and transcend Finality, what beckoned him was none other than a dream, which may at first seem like a dream of the past, but was in fact an expression of his own hopes and wishes for humanity’s future, beyond his own life and death.37

At last, we may now return to the riddle at the beginning of this article:

What do we talk about when we talk about dreams?

The two frameworks of dream analysis which I have presented throughout this article may not map quite so cleanly into night and day, but I hope you can see its relation to the multitude of dream logics and the different ways it connects to notions of desire and the unconscious. On the one hand, Freud’s psychoanalysis understands dreams as a form of wish-fulfilment in accordance to both the pleasure and reality principles, though he would later amend it to include the notion of the death drive, regardless of all the philosophical impasses that it would inevitably lead to. Of course, as we’ve discussed earlier on, these impasses ultimately stem from the fundamental philosophical assumptions that underpin the entire theoretical framework of psychoanalysis, which is to say the presupposition and prioritisation of the unity of the psyche.

On the other hand, Deleuze and Guattari critiqued this framework through the assertion that the psyche is, and always will be, incomplete; for that is precisely how it operates: by continually differentiating itself, opening itself up to that which is not itself through desire as a process of becoming, inseparable from the passage of time. Whereas life and desire exists in psychoanalysis for the sake of either pleasure or death, in schizoanalysis, desire flows for the sake of the process itself, goalless and directionless; and it is all the more directionless for the fact that it is heading inexorably towards the future, for that future in question is one that is still unformed and embryonic. As part of the flow of time itself, it is desire that creates that future; and so dreams, perhaps, could be said to be images of that emergent future that suffuse our present reality. In this sense then, is the story of HI3rd not one of those dreams that we seek to try to reach out towards the future?

In any case, I may have applied these frameworks in quite a generalised and perhaps even haphazard manner here, as I do not doubt that the writers of HI3rd are likely not thinking on these same exact lines when they were writing their story, although I would strongly argue - as I have also done elsewhere - that at the very least, the philosophy they were trying to communicate through the narrative of Part 1 of HI3rd is very similar, if not identical to what I have explored here.

Nevertheless, as I mentioned at the beginning of this article, I will continue to explore these themes and ideas in the second part of this article, where we’ll be taking a look at Part 2 of HI3rd and HSR’s Penacony storyline. By way of some more foreshadowing in that regard, instead of adhering strictly to frameworks of psychology and philosophy as I have done here, in the second part, I will also be borrowing a few concepts from some of the so-called ‘hard sciences’, such as the notion of thermodynamic entropy as well as the Many-Worlds Interpretation of quantum mechanics, among others.

After all, it wouldn’t be Honkai without a little bit - or a lot - of sci-fi, would it?

With all that being said then - whether it be Mars or Asdana - I hope to see you star-side, Dreamseekers.

solentestuaries is a writer, a fan of Honkai Impact 3rd, and one of the contributors in Hyperion Team 3rd. You can follow her social media at https://twitter.com/solentestuaries

Matt is Playing ‘Contract | Honkai Chapter 43, Hundred Years of Solitary Shadow’ (5 February 2024)

Kyu-Kyu, ‘The Sound and the Fury (Full playthrough) | Honkai Star Rail Version 2.0’, (7 February 2024)

Kyu-Kyu, ‘The Sound and the Fury (Full playthrough) | Honkai Star Rail Version 2.0’

Celestia Monarch, ‘Introduction To Psychoanalysis Hidden Achievement Honkai Star Rail’ (6 February 2024)

Pom-Pom’s Workstation, ‘Lustprinzip - Honkai: Star Rail 2.0 OST’ (7 February 2024)

Pom-Pom’s Workstation, ‘Realitätsprinzip - Honkai: Star Rail 2.0 OST’ (7 February 2024)

Honkai Star Rail, ‘Honkai Star Rail, ‘Knowing the Universe — “Approaching Dreams”’ | Honkai: Star Rail’ (3 February 2024)

Sigmund Freud, ‘Formulations on the Two Principles of Psychic Functioning’ (1911), in The Penguin Freud Reader, ed. by Adam Philips (2006) (pp. 414 - 421)

Freud, ‘Formulations on the Two Principles of Psychic Functioning’

Sigmund Freud, The Interpretation of Dreams (1899), trans. and ed. by James Strachey (1955)

miHoYo, Second Eruption, Chapters 49-51 (2022) [https://manga.honkaiimpact3.com/book/1005]

Maddoctor, ‘Honkai Impact 3rd Chapter 20 Immortal Phoenix Full CG, JP dub’ (7 May 2023)

Honkai Impact 3rd, ‘★Animated Short [Thus Spoke Apocalypse]★ Japanese-Dubbed - Honkai Impact 3rd’ (18 February 2022)

Freud, The Interpretation of Dreams

Maddoctor, ‘Honkai Impact 3rd Chapter 15 The Prodigal Girl Returns Full CG, JP dub’ (20 April 2023)

Maddoctor, ‘Honkai Impact 3rd Chapter 25 Set Tomorrow Ablaze Full CG, JP dub’ (28 June 2023)

Sigmund Freud, ‘Beyond the Pleasure Principle’ (1920), in The Penguin Freud Reader, ed. by Adam Philips (2006) (pp. 132 - 195)

Freud, ‘Beyond the Pleasure Principle’

Freud, ‘Beyond the Pleasure Principle’

Freud, ‘Beyond the Pleasure Principle’

Freud, ‘Beyond the Pleasure Principle’

Maddoctor, ‘Honkai Impact 3rd Chapter 25 Set Tomorrow Ablaze Full CG, JP dub’

Maddoctor, ‘Honkai Impact 3rd Chapter 11:EX Void Heavens & Diane's Sojourn Full CG, JP dub’ (11 April 2023)

Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guattari, Anti-Oedipus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia (1972), trans. by Robert Hurley, Mark Seem, and Helen R. Lane (1977)

Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guattari, A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia (1980), trans. by Brian Massumi (1987)

Maddoctor, ‘Honkai Impact 3rd Chapter 25 Set Tomorrow Ablaze Full CG, JP dub’

Honkai Impact 3rd, ‘Animated Short [Everlasting Flames] Japanese-Dubbed Edition - Honkai Impact 3rd’ (6 August 2021)

itsOgiru, ‘Honkai Impact 3rd Chapter 32 End of the World Act 3 Full CG JP Dub’ (21 November 2022)

Honkai Impact 3rd, ‘Honkai Impact 3rd Animated Short: Graduation Trip’ (3 March 2023)

Maddoctor, ‘Honkai Impact 3rd Chapter 20 Immortal Phoenix Full CG, JP dub’

Honkai Impact 3rd, ‘#HonkaiGLB3rdAnniv Honkai Impact 3rd Animated Short [Shattered Samsara] Japanese Dubbed Edition’ (27 February 2021)

Honkai Impact 3rd ‘Honkai Impact 3rd Animated Short: Because of You (Japanese-Dubbed)’ (9 September 2022)

itsOgiru, ‘Honkai Impact 3rd Chapter 34 The Moon's Origin and Finality Act 3 Full CG JP Dub’ (3 February 2023)

Honkai Impact 3rd, ‘★Animated Short [Thus Spoke Apocalypse]★ Japanese-Dubbed - Honkai Impact 3rd’

Honkai Impact 3rd, ‘Honkai Impact 3rd Animated Short: Graduation Trip’

itsOgiru, ‘Honkai Impact 3rd Chapter 35 Toward a New Tomorrow Act 1 Full CG JP Dub’ (10 March 2023)

itsOgiru, ‘Honkai Impact 3rd Chapter 35 Toward a New Tomorrow Act 2 Full CG JP Dub’ (16 March 2023)